- Home

- Kris Saknussemm

Sea Monkeys Page 3

Sea Monkeys Read online

Page 3

Poor Mr. Wyman, who gave me the hammer with a handle as blue as Pyramid Lake and a stiff white sailcloth bag for nails, ran the elevator in the Campanile on the campus at Cal Berkeley, the grand phallus of bell tower looming over the university, where if you looked quickly on the way up or down you could catch glimpses of the marvels stored on the other floors ... pieces of dinosaurs . . . old theater costumes . . . swords and Gold Rush tools.

When he wasn’t pounding nails and floating up through pines in someone else’s summer photos, maybe the work in the bell tower wasn’t so good for him . . . because he ended up committing suicide . . . jumping off the roof of one of the other buildings that he had the key to . . . he didn’t want to risk landing on someone from the Campanile. After that, they put up heavy glass reinforcement to make it almost impossible.

The tree house that he built for us still stands, and with my blue hammer, I took to pounding hornets, scooping yellow jackets from the surface of the bathtub the horses would drink from and crushing them (until I was swarmed and stung close to twenty times and almost died).

Like the cabin . . . those summers . . . our lives together . . . and Mr. Wyman himself . . . the blue hammer seems to dissolve in my hand . . . leaving only blue . . . the same blue the dog turned that morning on the road to Minden, Nevada, my father at the wheel of our blue Impala . . . the backseat and trailer filled with a summer’s worth of trash . . . from Cragmont cream soda cans to punctured archery targets.

We’re driving to the dump in the cool of the early morning and Dad is thinking about fishing the Carson River on the way back . . . buying a salt lick for the horses, a heavy tongue-pink cube with the image of a mountain embossed on it. Somewhere along the way, there’s a blue Ford pickup with a golden Labrador retriever in the bed, and cans of Sherwin-Williams paint, which I know from the huge neon globe down by the Aquatic Park in Emeryville, just off the Nimitz Freeway back home . . . all night a can of neon paint spills over the giant egg of the world and the lighted sign says WE COVER THE EARTH.

Suddenly, the truck swerves and rolls. Terrible twist and crunch of metal, branches scraping, grit of gravel . . . and my father spins the wheel. We crank back free into the morning shadow-blue of road, the trailer almost jackknifed but the hitch still intact. The truck plunges over the shoulder toward the river and I’m thinking that the dog is dead . . . but it finally bounds up through chokecherry barking blue . . . its coat stained a spirit unnatural dog color, and my father is flagging down a westbound truck to call for an ambulance, the wet blue of the dog all over my hands . . . all over my hands . . .

The same blue as the blue elephant keys they give to us kids at the zoo—big plastic skeleton keys with elephant handles that you insert in the speaker boxes beside each of the cages, which tell you a story about the animal inside.

The same blue as the background of the Blue Devil Fireworks stand in Yuba City, where the man with the retarded son sells Roman candles, skyrockets and sparklers . . . or the eyes of the chief in the Indian head of the Washoe Motel sign out on Highway 50.

It’s the same blue as the sky of Reno the night we drive my aunt and uncle to catch the train at the end of summer and we stop for dinner at a place called the Persian Room.

Like everywhere in Nevada, the place had slot machines and I was walking past one, going to the bathroom, proud to be going by myself—looking down at the patterns in the carpet—and without thinking about it, I pulled down a handle. I guess someone had left money in that machine, which mustn’t happen very often. But I pulled the silver arm down and three bright blue watermelons, those bizarre blue fruit you only find in gambling machines, cranked into the window with a satisfying whir and clunk. Jackpot. Twenty dollars. Jackpot!

A bell rang, and all of a sudden, change started cascading out—clanking wonderfully harsh and loud in the fat lip of the metal coin tray below. I froze, not knowing what to do. All the waitresses were dressed as belly dancers and one of them shimmered up to me. She was black and dressed in a gauzy, cloudy-blue veil covered with tiny bangles that caught the light. Her breasts were the biggest I’d ever seen. She leaned down to talk to me. She seemed so utterly real and yet I expected her to disappear in a wisp of smoke like a genie.

“You’ve got the luck,” she whispered and put her hand on me.

She touched me and we got a shock—a spark of electricity there in that blue hallway. She took me back to our table and she touched me again without my parents seeing. It embarrassed me because it reminded me of the woman who touched the hem of Jesus’s garment. And yet it thrilled me down deep in my little-boy loins. I can feel the cool blue fever of her even now.

The black lady is long gone. And the little white boy too. Only the blue remains.

DUST MELODY

I spent ages fascinated beyond measure by dust motes in the sunlight, lying on the floor next to Helen, my mother’s accompanist. O mio babbino caro. The music of dust—female feet in white and oxblood pumps working the pedals . . . my mother barefoot when she sang . . . the rhythmic streaming of endless miniature worlds.

Helen’s husband was a chemist for Shell and only drank milk, never alcohol. He played golf with my father, but didn’t seem much interested in the game. He liked to disappear off into the rough to collect lost balls. He’d recovered over five thousand golf balls over the years. He kept them in a closet in the garage, all freshly washed and piled in buckets, labeled with the name of the golf course where he’d found them.

They had a son who had a problem. They bought him a Lionel model train set to keep him occupied. He liked his trains. His green felt town. His certain little world.

Until something would go wrong around the water tower or the cattle crossing and then there’d be screaming. My mother would have moved away from opera to songs from musicals, like “Stranger in Paradise,” and suddenly a window would shatter upstairs. The golden dust of her singing would shudder and change shape, tiny pine trees and plastic cows flittering by the bay window, landing on the lawn. Then boxcars, flatcars, tanker cars smashing apart on the grass so that it looked like it had been raining model trains.

They always bought him new cars. They had the window fixed and fixed.

And every time there was an interruption, my mother would pause for a moment, as if she were waiting for the golden rivers of worlds to settle back into their steady dreaming—my little hands reaching through the bars and beams, amazed the whirling planets of dust could explode so softly and still heal back into their orbits, their flowing fall. Not like glass. Not like shark-nose locomotives or red cabooses. Like music I could hold.

SOLDIER IN THE EGG

All I could make of my cousin’s ravings was something about inspecting the Zone and collecting the dead snakes. Then I dreamed myself... of animals thrashing in a net made of something they couldn’t see. They were dying on a playground, I think—because of my confusion about the jungle—the only one I’d ever seen then was a jungle gym. My mother found me shivering in damp sheets.

I never told her the secret of my sympathetic delirium. I never even told my cousin Steve, the malarial Marine just home from Vietnam. But that afternoon, the nurses at Oak Knoll Naval Hospital had let me sponge him in his drowning.

He lay on his wet white bed in the room with drawn blinds, ranting about rock apes butchered by automatic fire—by which I came to understand he meant his platoon taking M-16s to the local baboons.

Only there are no baboons in Vietnam; they live in Africa. I’d find out years later that rock apes were some kind of legend that circulated among the soldiers. Maybe they were just monkeys that got blown away in fits of fear. Even Special Forces heroes lose their heads. But I believed him.

Finally, he fell asleep, gathering strength for another bout with the chills—the crossfire of a gunshot wound and the mosquito-borne blood disease. When his breathing slowed and his muscles relaxed, I dripped a drop of sweat from his navel into mine, and smeared it for the dark war magic I imagined.

&

nbsp; I was young enough to believe that sharing the fever would help cure his purple heart.

CALL TO WORSHIP

Come dusk and the white gnats, my father would muster the fishing gear and fade into a pale aurora of wild carrot and gin. To stand, no, to sway—his heart at home in the perfect, dynamic monotony of the river.

He was a hard man to admire, but coming upon him in the midst and the mist of fishing, it was impossible not to be awed. I’d watch him silently, never even whistling—not so much standing on ceremony, as momentarily rooted in it.

He was a fisherman of fossils and artifacts too. Trilobites, tree rings and Oligocene insects inside eggs of amber. When the trout weren’t biting, we looked for arrowheads. Because the secret of the past, he was fond of saying, is a fern frond pressed in a book of stone, at the bottom of what was once a lake of dreams.

Old man, young boy . . . there was always a lake of dreams.

DON’T GET A GUN, GET A BIG DOG

“Lor-raine? Is that you?” my mother asks.

She knows that the shadow almost out of sight on the second flight of our staircase isn’t my grandmother.

She knows, but she feels obliged to ask out of some misguided, middle-class faith in the normality of afternoon sunlight.

I’m playing on the floor with a plastic fire truck and my sister’s black patent-leather shoes. Not for long. My mother bundles us up without a word—me still clutching at the hot red plastic—my sister aware of an “emergency,” mature in spite of herself.

We head straight to the Gages, the big Catholic family next door. Soon, Sandy Gage is telephoning the police and we’re hiding at the window, waiting.

I watched him scale our backyard fence, a vindication of all the invisible evils I had warned my parents about, only to be dismissed as a child with a wild imagination. But there he was. At last, a monster of sorts—escaping, yes, but finally after others had seen him too.

And what a monster for a sunny afternoon.

He’d been there the whole time. He’d heard our pet names for ourselves. He knew that we were having Veal Birds in Bacon for dinner. He even knew of my impending birthday. And we knew nothing of him, except that he could stand very still, and that when we believed we were alone together—happy and sure of the familiarity of our lives, he was waiting on our back stairs.

I think my mother cried the first time I searched for a trace of his shadow. I admit I was standing at the window with the others when we watched him hop our fence. But having seen his shadow on the wall where my height was measured with pencil marks each birthday—how could I be sure he was gone? How could I be sure he was gone for good?

THE GHOSTS AND VAN CHEESE

I don’t think you could’ve had a better big sister. I can’t imagine one.

Back in the National Velvet In Search of Castaways Patty Duke past, she could draw well and was intensely inventive on a wide range of fronts. She created an entire scouting movement that included us and all the animals in the family and so was appropriately called Animals Combined (Cat Mandy, who gave birth to kittens Midnight and Wigwam, which for a while we got to keep . . . our German shepherd and dachshund . . . and John the Baptist, a box turtle, who was unfortunately flushed down the toilet during a mismanaged tank clean, for which I hang my head in shame). Each member had a special sash that she sewed, and there were literally hundreds of colorful merit badges to earn that she both invented and made by hand. And what unique ideas for merit badges. There was one that mixed rock-climbing with archery, and another that united puppet theater with safety. That was very much like my sister then—creating whole new categories of achievement. How many scouting programs do you know that reward you for remembering your dreams?

I got my first badge for saying “Fuzzy Wuzzy Was a Bear, Fuzzy Wuzzy Had No Hair, Fuzzy Wuzzy Wasn’t Fuzzy, Was He?” to bald Mr. Webb before I started laughing and ran away.

My sister was always fair. Our German shepherd received a merit badge for fishing when she leapt out of the boat with Dad in Angora Lake just as he was reeling in what he said was a monster steelhead but what was really a small rainbow (the dog helped Dad earn his boat rescue badge, too).

In my sister’s hands, our murky staircase (perfect for letting a Slinky down) turned into the Zambezi River, complete with waterfalls, pythons, pygmies and poison arrows. (Later, when the TV show The Time Tunnel came on, I once wrapped myself in a sheet and hurled myself down those stairs, hoping that I might find myself back at Gettysburg or in the Coliseum in Rome.)

My sister supervised my collections of rocks and minerals, seashells and belly button lint. She sewed two odd teardrop-shaped pillow creatures that were sort of like Laurel and Hardy. She was a wizard with Pig Latin, and once, when she found some vitamin E pills, she told me there were little skin divers inside so I spent hours staring at them with a magnifying glass. Like a blend of Hayley Mills (who was my first love) and Tintin, she was truly a savant and a leader.

She had a huge crush on James Drury, the star of The Virginian, and made the whole family go see him at a big horse show in the Cow Palace. She taught me the legend of Falling Rock in the backseat of our Rambler on our summertime travels. She showed me the key on the $1 bill. She taught me tiddlywinks, Red Light Green Light, Yahtzee—and songs like “Little Rabbit Foo Foo” and of course . . . On top of Spaghetti, all covered with cheese, I lost my poor meatball, when somebody sneezed.

She included me in all her playtime adventures with her friend Poppy (although one of the prices for this privilege was that they dressed me up like a girl once, complete with makeup and earrings, and made me climb up on the roof to retrieve their Wiffle ball).

And she was an early mix master on the vinyl record scene, demonstrating how on Bozo the Clown Under the Sea (an old 78 record) the voice of the Swordfish sounded like God when played at 33 rpm—or what we imagined God sounded like anyway. (Seventy-eight records, I hear you say . . . yes, well, in those days there were more things from other eras just lying around, although they were disappearing as we touched them, which is perhaps why we attached special value to them.)

My sister was more or less the secretary of entertainment for the family and was famous for her four-year-old rendition of Tennessee Ernie Ford’s “Sixteen Tons” in pink pajamas (which I’m very sorry I missed, although I did get to hear her do the theme song to 77 Sunset Strip). By the time I came along, we were of course inundated with Elvis and the Beatles, as was every other household in America, but we were honestly more partial to Herman’s Hermits and Chubby Checker (both of us were pretty good twisters—or rather I became a good twister under her direction). Our mutual favorite, though, was Dusty Springfield.

My sister had a little white suitcase record player and would play “I Only Want to Be with You” and dance to it while I climbed onto my squeaky rocking horse in my sleepers and enjoyed a kind of controlled epileptic swoon. It was a very bizarre sensation that overcame me then. A rise of adrenalin and probably a release of endorphins. Like the rush of possibility kids get on big ion days when it’s windy and warm—that sweet, sharp hint of ozone. I was intensely susceptible to this from my earliest memories, and music could simulate it. Early morning cirrus cloud hopefulness—or thunderstorm joy. My first sense of being high. And I think the first hint of the sexual buzz. We’d rock out and I’d ride like the little boy in “The Rocking Horse Winner,” forever gaining on some longed-for destination I had no idea about, only certain it was a kind of victory and deep knowing.

My sister had a special fascination for John Glenn, and, I believe, had she set her mind to it, she’d have made a fine space explorer (not to mention sinister mastermind or international spy). There was at that stage in our lives virtually nothing she couldn’t have done if the fit had taken her. She had more ideas than most R&D departments of the day.

Every Christmas, she’d read aloud the story called “Why the Chimes Rang.” And she read a lot to me generally—stories like “Thumbelina” and “William Tell

” and other tales from our Childcraft books (her favorite being “Bunny the Brave,” about a rabbit who outsmarts a vicious tiger, tricking him with his reflection in a pool of water). She wasn’t beyond occasionally taunting me, however, and one of the vehicles she deployed with deftness was a Time-Life coffee-table book on the wonders of the universe, which began with the immensely influential dinosaur illustrations of Charles R. Knight. (It’s hard to think of an artist who’s had more impact on both science and popular culture.) I naturally loved them. There’s something about giant reptiles and huge-eyed amphibians with dagger teeth. Those paintings opened up vast new vistas and formed an interesting contrast to the other two obsessive fascinations of the period: cowboys and space. Cowboys wrangling dinosaurs on distant planets (or in Live Oak Park) became a staple fantasy.

I see now that what unites them is some imagined sense of frontier. What I only implicitly appreciated was the aspect of nostalgia. A brontosaurus, six guns and a jet car . . . cavemen, box canyons, satellites . . . it was all the same dream really. Escape from the post-Eisenhower doldrums and the emerging tide of strangeness. A grasping at the future while clinging to the past . . . while reality slipped further away. My belief now is that all these luxuriant plastic growths and contagions were the aftershocks of Hiroshima and Nagasaki that shook our school and home windows like the sonic booms of those days (when’s the last time you heard a sonic boom?). The Cold War and the Dick Clark disease of television go claw in glove. A rain of lunchboxes fell out of those mushroom clouds. Dolls and dinosaurs . . . ray guns—fake Winchester rifles. I had a silver pistol that offered me gamma and beta ray options—and a pump-action toy shotgun “good for varmints” that was so loud I had to ask permission to fire it. “Becout, Mommy.” Boom. But I especially liked the megafauna in the Time-Life book—giant ground sloths in particular. I wanted very much to have a giant ground sloth—and I had the name all picked out. Beauregard.

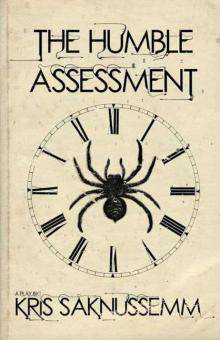

The Humble Assessment

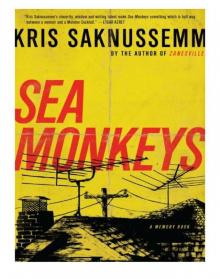

The Humble Assessment Sea Monkeys

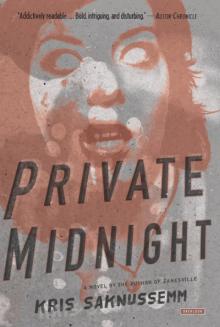

Sea Monkeys Private Midnight

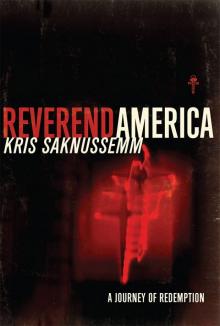

Private Midnight Reverend America: A Journey of Redemption

Reverend America: A Journey of Redemption Zanesville: A Novel

Zanesville: A Novel